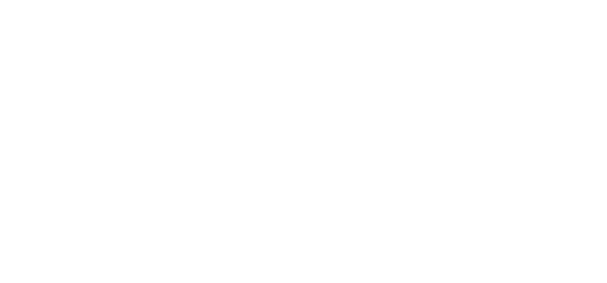

Charlie Clouser

Mastermind of Haunting Scores and Sonic Innovation

Photo by Justin Mohlman, Cleveland 2022

Charlie Clouser is a film composer, sound designer, synth programmer, keyboardist, and sound enthusiast, to name just a few, whose work has left an indelible mark on industrial rock and film scoring. Known for his interest in creating sounds never heard before and placing them in the precise place, Clouser has been, for years, crafting unique sonic palettes tailored to each project, blending heavily processed acoustic instruments, orchestral textures, and experimental techniques.

Photo by Zoe Wiseman, Los Angeles 2024

As the mastermind behind the haunting scores of the Saw film franchise, as well as other works, Clouser is recognised for his ability to evoke terror through unconventional means such as manipulating raw acoustic sounds, stretching them to their limits, and transforming them into dark, atmospheric soundscapes. He started going deeper in sonic exploration in his early days as a remix artist and synth programmer, working with bands like White Zombie and Prong, or with the well-known Nine Inch Nails (1994–2001).

Photo by Zoe Wiseman, Los Angeles 2024

As a true lifelong experimenter, Clouser describes himself as a „sound spelunker,“ diving deep into sonic caverns to uncover rare and evocative tones. His background in electronic music, coupled with years of mastering synthesizers like the Waldorf Quantum mk2, allows him to merge technology with creativity and to continue pushing the boundaries of sound design in music and film.

In Waldorf we consider him a friend, and we are truly happy that we had the honour to talk to him again and go a bit deeper in his work to share it with you. Enjoy!

Photo by Zoe Wiseman, Los Angeles 2024

Charlie Clouser

in conversation with Waldorf Music

Interview

with

Waldorf Music

How would you introduce yourself as an artist?

I’d like to be thought of as a sound spelunker, diving into dark caves in search of sonic gems. Sometimes I feel like a curator of strange sounds, almost like a painter who only does charcoal portraits with burnt sticks or something.

How did you start making music?

I had played piano and drums since childhood and went on to study electronic music in college, and from there the die was cast.

What was your first synth?

The first synth I played was a Sequential Circuits Pro-1 lent to me by the keyboard player in my terrible band in high school, but the first synth I owned was an Arp Solus mono-synth.

What inspires your music?

I’m always looking for a sound I’ve never heard before. Whether it’s a mean bass line, a scary ambience, or just a strange combination of elements, I’m just trying to find something I haven’t heard yet.

What’s your typical workflow when starting a new project, whether it’s a film score or a sound design commission?

The very first thing I do on a new scoring project is to create a batch of new sounds, inspired by the visuals and the story, that I can use as raw material for the music to come. Then I try to create a wire-frame structure of the entire project, with skeletal structures to indicate tempo, key, and rhythmic elements. I jump around in the timeline until every moment has at least been touched upon briefly before diving in to finishing any one portion. It’s sort of like drawing the outlines in a child’s coloring book, once those are done all that’s left is to decide if the clown’s nose should be orange or green!

Do you have a preferred instrument or technique to begin sketching ideas?

I start with very simple sounds for sketching, just semi-ordinary piano and strings, as well as the custom sounds made for that project, and once the “normal” music elements are sketched I can then move on to making things weird.

At what time of day or night will we meet you most often in your studio?

I am definitely a night owl. I work best once the world has quieted down and I can get a long chunk of uninterrupted time to make a mess out of the sounds.

What is the first thing you do when approaching a new synth?

The first thing I do is to read every single page of the manual with the synth at my side, just to make sure I know how to use every single feature. That way I don’t get into trouble when I have a precious sound half-finished, and I’m trying to save a patch or export a wavetable or whatever. Then I go through all the factory patches and ruthlessly delete most of them, keeping only the ones that use a cool programming technique or novel use of a feature. I don’t use factory presets, not even as a template for further modification, but I keep a few in the synth if they might remind me of a programming technique or feature that’s unique to that synth.

Using presets or patching your own sounds?

When it comes to synths, I’m always making my own sounds from scratch. After forty years I’ve almost figured out what all the knobs do!

What do you appreciate most in a synthesizer?

Mostly, the sound. Even a simple synth is a winner if it just sounds good to me. Beyond that I look for synths that push the envelope of modern features, like tempo-synced LFOs and envelopes, step sequencers for parameter changes, etc., and of course anything that can import a sample and wreck it will get my attention. That’s why I jumped on the Waldorf Quantum right away – to me, that synth represents the sum total of 50 years of synthesizer history. It’s amazing – and it sounds great!

What are your “must-have” tools in your studio? And what is your favorite piece of gear in your studio (other than a synth) that you can’t do without?

I’d be lost without a pair of good, characterful mic preamps, like my Neve 1084s or the new Overstayer Modular Channel Stereo, which can deliver hi-fi signals but can also wreck stuff on the way in.

What was your first interaction with Waldorf Music? You mentioned being in contact with Waldorf 30 years ago. Can you tell us more about how that relationship began?

I had a few PPG synths back in the 1980s, when the idea of wavetables was completely new and unique. They sounded great but were a bit fragile, so when PPG went away, and Waldorf began to improve upon the concept I was very excited. I had the first MicroWave rack synth, and Trent Reznor used it quite a bit on early Nine Inch Nails records. When I joined the band, Waldorf synths were a little hard to find, and we used to get them from an importer named Geoff Farr, who brought boutique synths into the USA, and from there I formed a relationship with the Waldorf team.

Have you ever collaborated directly with Waldorf on any product developments or given input on new features or designs?

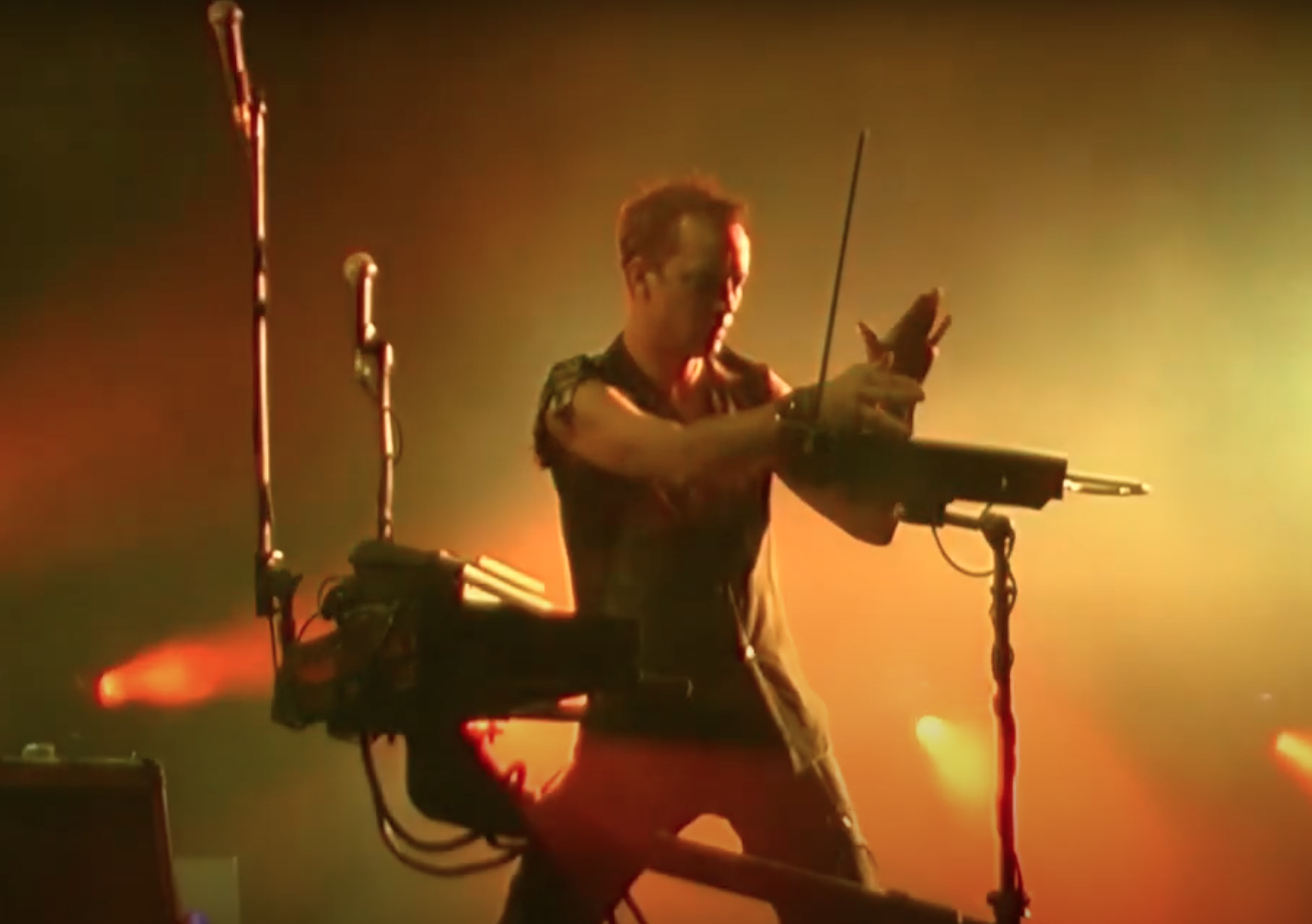

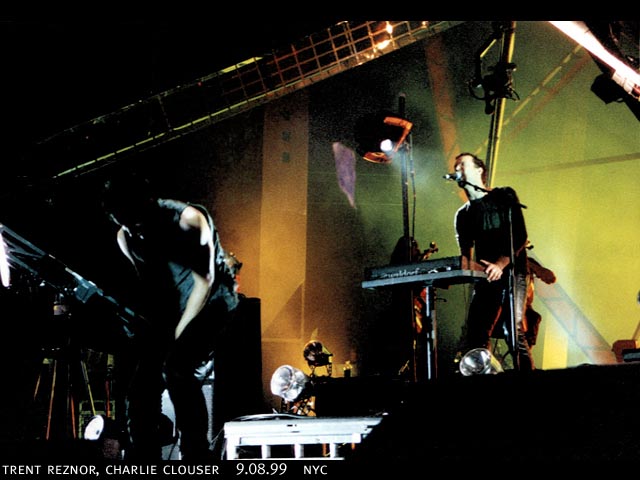

In the distant past I wasn’t really involved with Waldorf’s product development, but in 1999 they were kind enough to provide Nine Inch Nails with a pair of MicroWave IIxtk keyboards in a custom-painted grey “shadow” paint scheme for us to use on stage when NIN first played at the MTV Video Music Awards show. Since the normal paint scheme was bright orange, it didn’t really suit our dark on-stage aesthetic, and we thought that the shadow color would be a better match. I still have one of those two custom XTK keyboards and it’s still an amazing synth, capable of haunting ambiences and the most brutal industrial bass sounds. Since the release of their new Quantum synth, I have been communicating with Rolf at Waldorf to beg for a tiny feature here and there, and I did do a presentation at the NAMM show a few years ago to demonstrate why I thought it was such an amazing synth, using some of the features and programming techniques that might be less obvious to some.

Looking back, how do you think Waldorf synths had influenced your approach to sound design and composition over the years?

The Waldorf synths have always provided a path that’s a bit to the left of the more mainstream synths like Roland or Korg, offering the ability to get to places that other developers fear to tread. Besides being an early innovator of synths capable of creating “evolving textures”, their synths have always been able to do the most brutal and heavy industrial tones and the hardest and sharpest sequenced patches. Their attack is unmatched! And that spectrum of capabilities nicely matches what I’m looking for in the music I’ve been involved with over the decades, so it’s no surprise that I’ve always had a bunch of Waldorf gear in front of me.

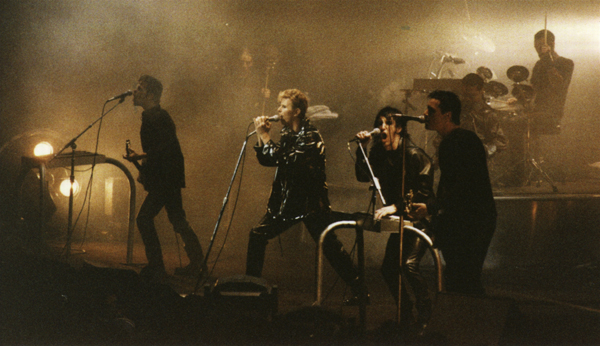

Charlie with NIN at the 1999 MTV VMAs, playing the custom Waldorf Shadow MicroWave 2XTk. Photo by Rob Sheridan.

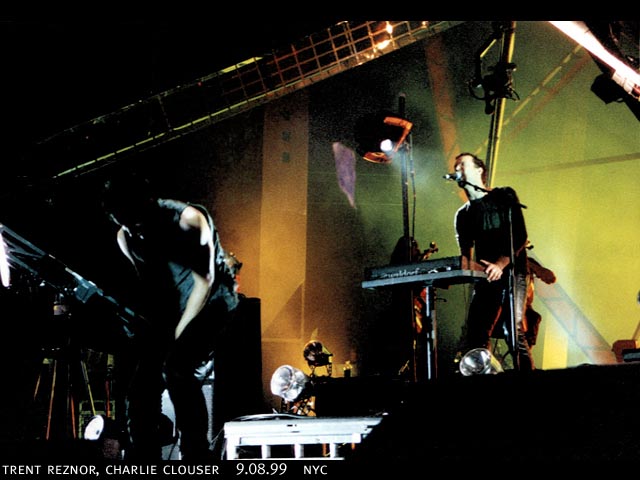

Customized Shadow MicroWave 2XTk that Waldorf made for NIN. Photo by Charlie Clouser.

Have you ever collaborated directly with Waldorf on any product developments or given input on new features or designs?

In the distant past I wasn’t really involved with Waldorf’s product development, but in 1999 they were kind enough to provide Nine Inch Nails with a pair of MicroWave IIxtk keyboards in a custom-painted grey “shadow” paint scheme for us to use on stage when NIN first played at the MTV Video Music Awards show. Since the normal paint scheme was bright orange, it didn’t really suit our dark on-stage aesthetic, and we thought that the shadow color would be a better match. I still have one of those two custom XTK keyboards and it’s still an amazing synth, capable of haunting ambiences and the most brutal industrial bass sounds. Since the release of their new Quantum synth, I have been communicating with Rolf at Waldorf to beg for a tiny feature here and there, and I did do a presentation at the NAMM show a few years ago to demonstrate why I thought it was such an amazing synth, using some of the features and programming techniques that might be less obvious to some.

Charlie with NIN at the 1999 MTV VMAs, playing the custom Waldorf Shadow MicroWave 2XTk. Photo by Rob Sheridan.

Looking back, how do you think Waldorf synths had influenced your approach to sound design and composition over the years?

The Waldorf synths have always provided a path that’s a bit to the left of the more mainstream synths like Roland or Korg, offering the ability to get to places that other developers fear to tread. Besides being an early innovator of synths capable of creating “evolving textures”, their synths have always been able to do the most brutal and heavy industrial tones and the hardest and sharpest sequenced patches. Their attack is unmatched! And that spectrum of capabilities nicely matches what I’m looking for in the music I’ve been involved with over the decades, so it’s no surprise that I’ve always had a bunch of Waldorf gear in front of me.

Customized Shadow MicroWave 2XTk that Waldorf made for NIN. Photo by Charlie Clouser.

And what role do Waldorf synths play in your music nowadays?

Now that I’m concentrating mostly on scoring for picture, the Waldorf Quantum mk2 is my primary weapon. It allows me to take audio samples that I’ve created from my custom acoustic instruments, or wild orchestral effects sounds, and manipulate them with unmatched flexibility, stretching and granulating and filtering to my heart’s content. That way I can preserve some of the organic sonic footprint of the sounds I like, but create entirely new textures that don’t sound like a normal oscillator+filter synth, and that’s key to my whole way of working. I use the Quantum to create many of the standout sounds that are at the front of a piece of music, sometimes entire film cues at once. The poly-aftertouch on the mk2 has really opened up the possibilities for expressive use of these custom sounds and I love the thing. It’s front and center in my setup.

Your background spans electronic music, rock, and film. How do these different worlds converge in your creative process?

The common thread through all of my musical adventures has been looking for the darkness and heaviness. The music of NIN was heavy at times, but it was also quite atmospheric and unique sound design was always a big part of the picture. I think that’s why I was a good fit at the time, because I’ve always been into really heavy, dirty sounds full of destructive force, but I also enjoyed exploring darkness in more atmospheric textures. As I moved more into scoring for horror films, those same elements played a big part. Perhaps less on the destructive side and more on the atmospheric side, but still originating from the scope of what I had done with NIN.

As someone fascinated by unheard and unusual sounds, how do you stay curious and push the boundaries of what’s possible in sound design?

There are always going to be new sounds to discover, so the thirst to discover them will never be satisfied. With the amazing tools we have these days to manipulate sound, I get excited on a daily basis about what I might find. It seems that every week I get excited about some new processing plugin or guitar pedal, and call all my friends to say, “Have you heard this thing yet? It’s amazing!” I still feel like a kid in a candy store.

Sometimes you’ve mentioned that creating a unique set of sounds for each project is essential. Can you walk us through your process for designing a project-specific sound library?

If I’m scoring a new film, I’ll watch it a few times through, and then put it on a loop so it’s playing on the wall while I mess about with sounds. I’m always hoping that the visual style, the cinematography, and the settings in the film will influence the direction I’m going in with the sounds. I definitely picture sounds as belonging to a place, as sounding “outdoors” or “underground” or “forest” or “city”, and it’s really easy for me to hear something and think, “No, that’s wrong for this scene because it sounds like it’s outdoors, it reminds me of a winter landscape” or whatever. Maybe I have a touch of synesthesia, I don’t know what it is, but I form those opinions almost instantly upon hearing a sound, and I try to use that to guide me as I’m spelunking, in the hopes that the sounds I use will be appropriate for the places depicted on screen.

In the Saw scores, for example, you use heavily processed acoustic and orchestral sounds. How do you decide on the sonic palette for a particular project?

Again, I’m heavily influenced by wanting a sense of place for the sounds, so they seem like they belong in the frame of the image we’re seeing. For the SAW movies this is usually pretty easy, since most of the scenes take place in some dank dungeon, or some other unlit room. So, darkness, reverb, and a rusty patina to the sounds usually feels right. I use a lot of bowed metal sound sources and rusty-pipe percussion type sounds, inspired by the machinery that our villain builds for his traps, so those choices kind of jump off the screen and into the keyboard it seems.

You’re known for creating terrifying and evocative soundscapes. What’s the most unusual sound source you’ve worked with, and how did you incorporate it into your work?

I do have a few custom metal instruments built by an amazing musician and instrument builder named Chas Smith, who sadly passed away recently, and I guess those are unusual since they are truly one-of-a-kind creations, but some of my favorite oddball sounds are recordings I made in the NYC subway about 35 years ago on a cassette recorder. They’re the sounds of the train’s brakes squealing as the train pulls into the station, sort of a nails-on-chalkboard sound that will be familiar to any city dweller. Drenched in the natural reverb of the subway tunnel, these recordings are surprisingly tonal and have a fairly stable pitch. When they’re slowed down and pitched down in a sampler, they begin to sound like a wobbly, murky, distant string section, and I have used bits and pieces of these recordings on dozens of projects over the years. Those subway-tunnel sounds were the first samples I imported into the Quantum, they’re the perfect raw material to be transformed inside the Quantum.

From Nine Inch Nails to scoring films, your career has had remarkable twists. What advice would you give to emerging sound designers or composers looking to carve out a unique path?

All of the weird twists and turns I’ve been lucky enough to follow, all the opportunities that I’ve been able to capitalize on, came to me because I didn’t want to do anything that other people were already doing very well, I didn’t want to be a beginner among experts. So, whenever I discovered something that others were doing very well, I’d try to steer a little off to the side, if not drive off the road entirely. So instead of cruising down the well-travelled path at highway speeds, watching other people’s tail lights receding into the distance as I tried to keep up with them, I often found myself crashing through the bushes, trying not to get stuck in the mud. This made my progress slower in some spots, but meant that I often had the trail to myself. In terms of advice, this all boils down to that old chestnut: find your own sound, your own path. As corny as it seems, that’s what is at the core of all the things I’ve been involved in – trying to avoid doing what others are already doing well.

What’s a project you’re particularly proud of, and why?

One of my favorite film scores that I’ve done was to a small movie that few, if any, people saw. It was my second score, for a movie called Deepwater, and I’m not even sure if it ever was released. I had the time and the freedom to experiment, and I managed to create some long, intense, rhythmic passages by tapping guitars with pencils into a looper pedal and then processing the results, as well as some dissonant brass-like chords made by reversing and layering acoustic guitar chords. I also used some circuit-bent toy instruments for scenes where the main character was having a mental break, and these really worked well – it sounded like what was going through his fractured mind as he struggled with reality. I was really just experimenting and finding new sounds and it worked out great, even if nobody saw the film. I did some things on that score that I’m still trying to recreate for other projects to this day!

If you could revisit any stage of your career with today’s technology, what would you create or experiment with?

Weirdly, I wouldn’t want to go back to the early NIN albums with more modern tech, since it was the limitations of the machinery that pushed us towards certain results, and the analog tape recording and all-analog mixing that gave those records a certain sound. So, I wouldn’t touch those records with any gear, for any price. But I wouldn’t mind having the faster computers and more advanced tools for tricky projects like the albums and remixes I worked on with Rob Zombie, Helmet, and other heavy bands. I was always hitting the limits of what I could do with X number of ProTools tracks or Y amount of sample memory.

What project are you currently working on? (January 2025)

While I’m waiting to see if and when an eleventh movie in the SAW franchise gets made, I’m actually returning to the road and playing keyboards live with the band Ministry, who are industrial music pioneers and were a big influence on NIN in the early years. Their keyboardist and synth programmer for the last 20 years or so is one of my oldest friends in the world, John Bechdel. We were buddies in college in the early 1980s, roommates in NYC after college, and both worked at the same music store in Manhattan where we’d buy used PPG synths for pennies on the dollar, back when people wanted to trade them in for a DX-7 or whatever! So, it’s a bit like coming full circle since it was more than 40 years since we’d been in the same band at the same time. Crazy how things work out sometimes.